[ad_1]

Legitimacy is a very difficult thing: it cannot be measured in any way, and a lot depends on it.

How informs Wikipedia, “legitimacy is the consent of the people with the authorities, their voluntary recognition of their right to make binding decisions.” Where does it come from? From the elections. And not even from the elections themselves, but from their perception by people. “Why do we obey the minister or the governor, although we do not know them, and if we do know, then we justly consider swindlers and thieves? Therefore, Putin appointed them. And, whatever one may say, people voted for Putin ”- this is approximately such a mental dialogue in the last few years that has been typical for an opposition-minded man in the street. And in many ways this was true. If, say, even look at Shpilkin’s famous graphs of elections to the State Duma in 2016 and for the presidential elections in 2018, huge falsifications are visible there (10-12 million votes each were thrown in favor of United Russia and Putin), but at the same time something else is visible: if it were not for all these falsifications, United Russia and Putin would have won anyway. Their victories would not have been so devastating and impressive, it would have looked worse from a propaganda point of view, but, nevertheless, most of the voters who came to the polling stations and who cast their votes then supported the authorities.

This is no longer the case – and this is the main political outcome of the elections to the State Duma in 2021. Volume of falsifications increased not so much (14 million votes cast in – terrible if you think about it, but not so much worse than three or five years ago), but their value has grown immeasurably. Because without falsification, this time United Russia failed miserably, gaining less than a third of the votes on party lists and losing about 70-80 single-mandate constituencies, that is, losing even a simple (and not just constitutional) majority in the State Duma. The smart vote in September 2021 won a big political victory.

Did we understand that there would be falsifications? Of course, well, we didn’t fall from Mars. But we expected that, thanks to Smart Voting, the Kremlin would have to make such significant and visible falsifications that it would significantly undermine the legitimacy of the government. That you will not be able to steal elections unnoticed. Did we succeed in this? In order to understand how Russian society actually perceives the results of the elections to the State Duma, we conducted in hot pursuit, almost after the elections, another telephone survey of Russian voters (based on a representative sample of 1000 people). Let’s take a look at the results of this survey together.

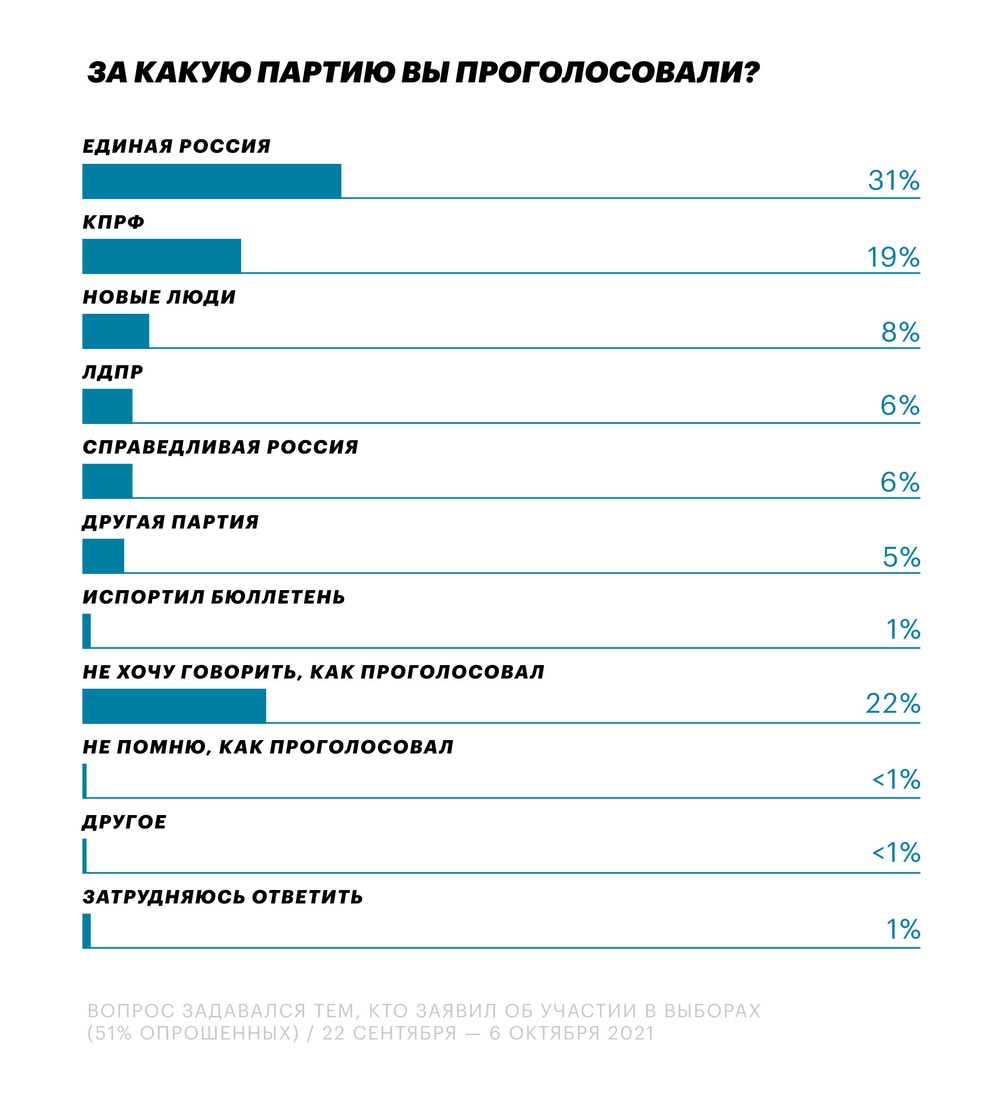

On the first slide, there is nothing surprising. Well, or everything is surprising, it really depends on how you look at it. We asked the simplest question: “dear voter, how did you vote?” The question was asked 1-2 weeks after the very elections in which, according to the official data of the Central Election Commission, United Russia won a landslide victory, gaining 49.8% of the vote. But here’s the bad luck: for some reason, in a telephone survey, the fact of voting for United Russia was confirmed by only 31% of respondents. Striking discrepancy with the official CEC data … striking coincidence with the results of mathematical modeling, rejecting falsification. However, according to all the same data from Shpilkin, it turned out that in reality almost as many voters voted for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation as for United Russia, and we have a big gap on the slide. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation is the second, with 19% of the votes. Why is that? We look further and see: as many as 22% of the respondents who took part in the elections, refuse to say by phone how they voted. That is, they are afraid.

This is big news: it is not the first year that we have been doing post-election polls in order to check the official results and get a real picture of what happened, but this is the first time we have seen this. Fear. Every fifth voter – of those who have already agreed to talk on the phone with a sociologist and answered positively to the question about participation in the elections – did not dare to say what choice he made. This has never happened.

And there can be only one explanation here: people are afraid. They are afraid because they expect reprisals for the “wrong” answer. And, of course, this means that within these 22% there is a protest vote: one can safely assume that almost all of these people did not vote for United Russia, but one can hardly say anything confidently about the proportion the votes of these “refuseniks” were actually distributed among other parties. One thing is clear: the real result of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, the Liberal Democratic Party, the SRHP and the “New People” was higher than shown on our slide. And, by the way, pay attention – probably, “New People” actually took the third (!) Place. This was the case almost everywhere in those regions of the Far East and Siberia, which are traditionally the least affected by falsifications – and our survey showed that, apparently, this was the case throughout Russia.

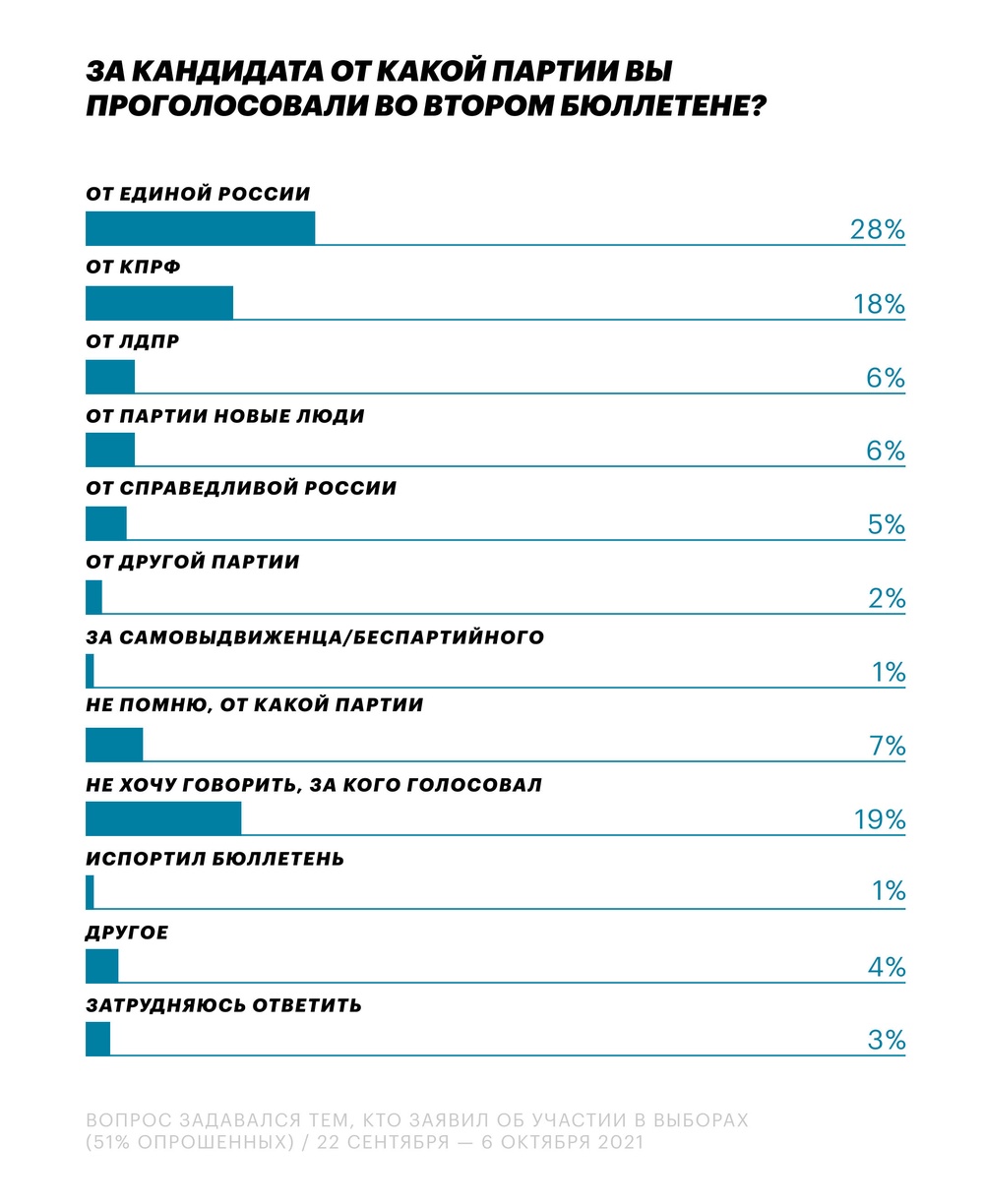

For control, we also asked a question about voting in single-mandate constituencies: here the picture is generally the same, and the result of United Russia is even less.

And now about the main thing: about the legitimacy of the authorities after these elections, about their perception by voters.

A quarter of the respondents say that they are “dissatisfied” with the election results, and in general, 37% of Russians are “rather dissatisfied or dissatisfied”, while 47% are “satisfied or rather satisfied”. Somehow, there is no nationwide unity and jubilation. Moreover, the overall percentage of those satisfied with the election results is less than, according to official figures, United Russia received. That is, it turns out that many people (according to the CEC) voted for United Russia, but they are not happy with the victory of their party … Strange!

But we see an even more vivid picture of what happened when we ask our respondents a direct question about their assessment of the fairness of the elections:

And we have been asking this question for many years every time after major elections. And we have never seen such a thing. In short, Ella Alexandrovna, this is a fiasco. You have failed everything, Kiriyenko and Putin will drive you without severance pay. How many billions of rubles, how many propaganda tricks and gimmicks have you invested in explaining to the Russians that we have the most honest, democratic and wonderful elections in the world – and the Russians did not believe you. You didn’t succeed. Half of Russian voters believe that the official election results do not reflect the real opinion of citizens – and only a third believe in the honesty of elections and vote counting. The option “do not reflect,” the winner by a huge margin, with 39% of the answers, are those people who understand that the elections are absolutely drawn. And there are twice as many of them as 18% who believe in the fairness of the elections without a shadow of a doubt.

Mockery of the elections, the fight against “Smart Vote”, the desire by all means to draw a beautiful result for “United Russia” – all this cost Putin too dearly. A serious blow has been dealt to the legitimacy of the Russian authorities; after September 19, 2021, most Russians know that they are ruled by a parliament that they did not elect; that the deputies are thieves who stole mandates. This is an important, watershed change in public opinion that will have lasting consequences; they will not necessarily appear immediately, but sooner or later they will.

As long as nothing special happens in the political life of the country, the situation may seem stable. But sooner or later, any government in any country faces crises, within which it has to make unpopular decisions; and this is where legitimacy begins to play a huge role. A power that has lost its legitimacy turns out to be a colossus with feet of clay: people simply refuse to accept unpopular decisions from the hands of such power. And any crisis can therefore become a turning point.

…

[ad_2]

Source link